It was a long time ago that game wardens developed the ingenious idea of mounting the hide of a big game animal on a robotic frame that could move its head and flick its tail. Place the decoy 25 yards from a rural roadway and put reflective mirrors behind the robotic model’s eyes, and you’ve got robo-deer that works day or night.

Thousands of bad guys throughout the nation have pulled the trigger on robo-deer and its relatives, securing convictions for crimes like poaching, spotlighting, shooting over a roadway, shooting from a vehicle, and driving with a loaded weapon.

In fact, sting operations involving robo-decoys have been so successful that poachers are wising up to the trick.

Fortunately, game wardens have the latest advances in technology at their disposal to develop new ways to catch poachers trying to outsmart the law. This includes everything from human-recognition software in night vision surveillance cameras to acoustic systems that are able to detect bullets and pinpoint their firing location.

Here’s five developments game wardens are using that should make poachers think twice before trying to bag game illegally.

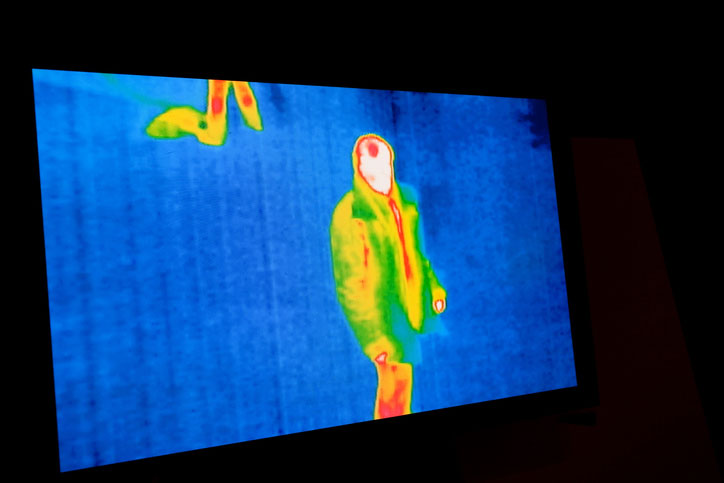

Thermal Imaging Cameras

Infra-red cameras that detect heat have been used by the military and law enforcement for decades. What’s new is that today computer software can be combined with these to automatically detect humans and sound an alarm.

Cameras with this software installed can be set up at bottleneck points, on hilltops, or along roads where would-be poachers might frequent. When the cameras detect a human presence based on the shape and movement characteristics of a surveyed target, they alert game wardens who can then determine a possible intent to poach.

With a zoom lens and the ability to detect poachers in the dead of night from up to one mile away, these new types of cameras have already proven to be game-changers in some areas. They also allow game wardens to approach poachers with the complete stealth of darkness.

These cameras were recently debuted at a wildlife reserve in Kenya as part of the World Wildlife Federation’s Crime Technology Project and have already resulted in the arrest of more than 24 poachers.

Upgrades to detect specific animals instead of humans can also be developed for this camera system, potentially giving wildlife officers a tool to help with animal population surveys and migratory mapping.

Ballistic Shockwave Sensors

These types of sensors are already installed in places like Washington DC and other major cities throughout the world where gun violence is rampant. They work on the same principle that seismographs use to detect shockwaves from an earthquake that travel through the ground.

The report of gunfire creates shockwaves that travel through the air. Because they go so fast, bullets also make their own shockwaves. Thanks to advances in technology we now have devices that are sensitive enough to detect these ballistic shockwaves that move through the air.

When a ballistic shockwave is detected the sensor sends a notification to game wardens. With an array of detectors set up throughout an area, game enforcement can use data from at least three points to triangulate the exact geo-location of where a gunshot has been fired.

Some have even taken to installing ballistic shockwave sensors on animals themselves. As part of a collaborative project between Vanderbilt University and Colorado State University, a team tranquilized elephants in Kenya and installed these senors on their heads along with GPS location collars.

Ballistic shockwave sensors can detect gunshots from as far away as 275 yards, and possibly further depending on local environmental conditions.

Drones

Drones used to be reserved for model airplane hobbyists and militaries. Not only have the Border Patrol and municipal police departments also taken advantage of the current drone upsurge; wildlife conservation officers and game wardens are also using these latest technological developments.

Drones bring several advantages with them for game protection, chiefly an eye in the sky that can record evidence. They can also be fitted with some of the technological advances we’ve mentioned like infra-red heat detection cameras for night vision, zoom cameras, and shockwave acoustic sensors.

Drones come as fixed-wing and quadcopter aircraft. Fixed-wing drones are more expensive but they can stay aloft longer and cover a much larger territory than quadcopters. They can go as high as 20,000 feet, be controlled from as far away as 60 miles, and fly quietly for hours on end unbeknownst to their target.

Wildlife protection groups and conservation officers are already using drones to counter poachers and tally wildlife populations in nature reserves in Kenya, Sumatra, and Canada to name just a few countries.

Some states have made movements to develop their own drone programs for game wardens. Alabama was perhaps the first, with the governor forming a task force in 2015 to study how the state’s law enforcement and conservation officers can improve their effectiveness through the use of drones.

Ironically, game wardens may not be the only ones deploying drones out there. Some states allow hunters to use drones to locate game animals like deer. Conversely, game spotting with drones has also been made illegal for hunters in other states.

DNA Analysis

Recent advances in DNA analysis technology is shaping up to revolutionize how game wardens fight poachers.

Using DNA samples collected from an anesthetized big game animal combined with radio transmitter tracking, forensic biologists are able to create a detailed geographic map of a herd’s territory. Doing this over a large area allows them to make a location-specific database of entire animal populations and herd families.

So for example, if a game warden finds someone in possession of a bear paw, that officer can run the bear’s DNA through the database to determine where it came from. If the bear – or even the bear’s relative – is in the database, game wardens can determine a very specific location for where they may find the bear’s body.

If they are able to locate that kind of physical evidence, they can send the poacher to jail for a longer time. And even if they aren’t able to locate the bear’s body, they can alert other game wardens in the area to be on the lookout for poachers, especially if multiple bear parts are found to have been poached from a certain region.

Perhaps the country with the most advanced animal DNA database is South Africa, which maintains its RhODIS system (Rhino DNA Index System). When a suspect is found to be in possession of a rhino horn, the authorities start by running it through their database.

Until the implementation of RhODIS a poacher would often claim to have found the rhino horn laying on the ground. Now game wardens are sometimes able to use the DNA profile of the rhino horn to locate its body and bring much more serious charges against the poacher.

Vital Sign Monitoring in Real Time

This one seems hard to believe, but some conservation groups are actually embedding heart monitors in big game. That’s right. Once the animal’s heart stops, whoever is monitoring the live feed gets an alert.

What’s more, such devices are being linked with other high-tech tools like video cameras, microphones, and GPS collars. One group in South Africa is testing a system that involves many of these elements combined.

The conservation group Protect from the UK has deployed an embedded heart rate monitor into a population of rhinos. Once a rhino’s heart rate becomes too fast or slow, the heart rate monitor alerts the team and they remotely activate a camera that has been installed in a bore hole in the rhino’s horn. If it appears there is a poaching event underway the team at Protect alerts game wardens and vectors them into the rhino’s GPS coordinates.

While this system is currently under development and being tested, Protect hopes to install it in populations of African elephants, tigers in India, and even predatory birds in England.

Even if the heart rate monitors might seem over the top, the methods and software developed for this type of integrated system alone will undoubtedly have an impact on wildlife poaching and future developments by integrating geo-location with audio and video evidence.